Eorzea Shines Through: The Art of Final Fantasy XIV

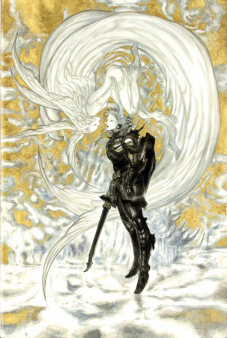

I remember when the original Final Fantasy XIV came out in 2010. I handed over my gil and excitedly set about installing it. My last image before delving into the game itself was of the collector’s edition cover art, which featured a beautiful image by Yoshitaka Amano.

Amano has been the main logo and character designer for most, if not all, of the Final Fantasy franchise. Because of his prolific work with the series, his distinctive fantasy style is perhaps more evocative of Final Fantasy than any other game, comic, or project he has worked on. The series is one of the most successful RPG franchises in history, and Amano’s artwork evokes the sense of wonder fans have come to expect of its beloved characters, worlds, and narratives. In a sense, the artwork is not merely associated with Final Fantasy, but becomes it. And so the collector’s edition cover art spoke for all the hope and promise the game so sorely failed to deliver on.

The original Final Fantasy XIV was bogged down by so many clunky systems, few players could even get off the ground. I never got a handle on the crafting system. Leveling became a chore. The usually simple act of equipping items was hampered by a clunky interface. It wasn’t any fun. Pretty soon, I hit a wall. The promise had failed. The game bombed with critics, scoring an average of 49 out of 100 on Metacritic, and sold disastrously for two years before being completely rebooted in the form of Final Fantasy XIV: A Realm Reborn in 2013.

The reboot was a success, and this year counts more than five million active subscriptions worldwide, myself one of them. However, as big a failure as the original Final Fantasy XIV was as a game, I argue that Amano’s artwork still succeeds in expressing the idea of Final Fantasy.

The idea of Final Fantasy is ineffable, but players know it when they see, hear, and play it. It’s Amano’s fantasy art, composer Nobuo Uematsu’s signature theme, and old-school RPG mechanics. It’s heroes of light, chocobos, and airships woven together in an epic narrative. It’s also change: turn-based to real-time battles and all new characters and settings alongside familiar elements. This idea extends from the first Final Fantasy to its decades of direct and spiritual successors, and even other RPGs. It extends beyond the gameplay and graphics wired into its software to its concept and promotional art, toys, soundtracks, and other merchandise, as well as to fanfiction, fan art, and players’ imaginations.

Akihiko Yoshida Gallery

Artwork is the one element that not only works powerfully to exhibit a game’s idea but also constitutes the last of its appendages the player encounters before s/he enters the game itself. It serves to fashion a game’s visual style but also advertises it on the cover art, even down to the label of the cartridge/disk or the digital variant’s title menu. The game and its artwork should ultimately be one with the game’s idea, but this isn’t always the case. The original Final Fantasy XIV highlights just such a failure to connect.

Final Fantasy XIV: A Realm Reborn still features Amano as a lead artist but also includes a cast of other talented artists, including Akihiko Yoshida, Kazuya Takahashi, and Ayumi Namae, among several others.

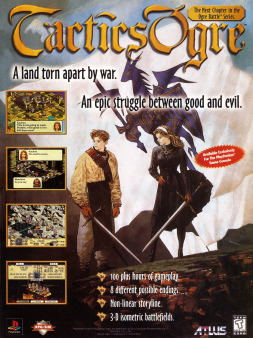

After Amano, Yoshida is perhaps the most well-known and prolific artist in the Final Fantasy franchise and its close cousins, having worked on Tactics Ogre, Final Fantasy Tactics, and Final Fantasy XII, among other titles. While not strictly a part of the franchise, Tactics Ogre is certainly in the vein of the old-school tactical RPG. It became the model for Final Fantasy Tactics and bears similar artistic styles and narrative themes to the Final Fantasy series.

Advertising artwork for Tactics Ogre features the main character Denam Pavel and his sister Datiua nobly foregrounded by the flag of Walister, a blue knighted dragon on a field of white. Their figure behavior amidst these signs signifies a readiness at arms, whilst dark clouds in the background foreshadow conflict. The image calls for the player to take up arms in a medieval-inspired war. The accompanying screenshots are associated with the illustration, translating the idea into gameplay while also projecting onto it fantasy elements through the depiction of a mid-action fire spell.

It is important to remember that this association is arbitrary. The screenshots themselves bear no immediate resemblance to the illustration. One is drawn, while the other expressed as ably as allowed by the hardware limitations of the system. These graphical depictions are described by critic Alexander Galloway as “machinic embodiments,” outward expressions of the original PlayStation’s hardware capabilities. It is why one might look at any screenshot of the game or the similarly styled Final Fantasy Tactics and more than not compare the graphics to something like the PlayStation or PlayStation Portable, because they are par for the course within the graphical limitations of the time. While Yoshida worked on the design of the digitized characters, and while the illustrations that accompany in-game dialogue may be more representative of the larger illustration, their actual association in this advertising piece is ultimately formed by the images’ shared expression of the idea of Tactics Ogre as it extends within gameplay and outside of it, rather than solely through the screenshots and illustration displayed in the advertisement.

Yoshitaka Amano Gallery

This advertisement denotes the game, but its consumption doesn’t stop there. Instead, the illustration embodies a charged expectancy that the idea lies further ahead at the site of gameplay, wherein the screenshots and their contents might be found. No doubt, many consumers did so, and it is this travel from concept/promotional artwork to the visual design of the game itself that works to meld the two into a single construction, or its idea.

Another image by Yoshida works similarly, here from the June 2014 cover of PlayStation magazine. Like Denam and Datiua, our foregrounded representative player character (who could be any other race and class), stands amidst the various non-player characters (NPCs) whose figure behaviors all look toward their own epic narrative. The dragoon Kaine holds some talisman, while other characters look toward their own individual fates. Again, an ominous cloud fills the sky, foreboding antagonism. Like brother and sister in Tactics Ogre, these characters are united. It’s a composition not unlike many adventure movie advertisements. Star Wars movie posters might immediately come to mind. The charged expectancy here, especially for an MMORPG, is one of cooperative play.

Final Fantasy XI and XIV aren’t the only games that promote cooperative play. Most, if not all, MMORPGs feature a party of characters who work together to overcome some larger evil, oftentimes in the form of a ruthless empire. Final Fantasy XII is one clear example on the traditional RPG side, but Final Fantasy XIV and MMORPGs in general accomplish this with a greater sense of cooperation—with larger parties, every member of which is set forth via human agency, and whole servers full of participants on similar journeys. The job system is also integral to just about every entry in the franchise, and speaks to cooperation. To choose a Paladin is not to choose a Rogue. Parties must form accordingly if they hope to have the right balance to thwart their enemies. This dynamic is present in any MMORPG; to choose a tank class is not to choose a healer, and so forth.

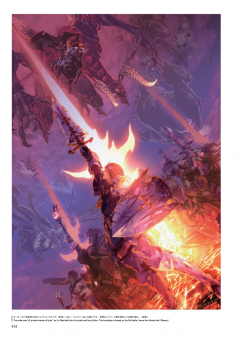

Our last image is by the artist Kazuya Takahashi and sums up nicely the associative qualities of illustrative art and gameplay, as well as the spirit of cooperation that are just some elements of the idea of Final Fantasy and similar games. In this image, warriors of many jobs band together against several primals, blazingly lit by Ifrit’s Inferno Nail. In the game, the Inferno Nail must be destroyed quickly or else the primal nearly always wipes the party. On a harder difficulty setting, with a larger party, multiple nails must be taken out.

Unlike in the last two images, the party here is actively engaged in combat against its foes. Ironically, the Inferno Nail—an enemy device—acts like the flag of Walister from Tactics Ogre, a sort of banner accentuating the warriors’ formation. The combat is presented in an exaggerated sense. Typically, a smaller party fights against one primal at a time in its own arena. Here, we have more of an alliance of players preparing to fight in all the showdowns at once, playing the game not progressively but entirely. Thus, the image works harder than the game, providing a great deal of gameplay expectancy—cooperatively—in the single illustration. All illustrations do this to some extent; they take up physical space and can only promise what can be delivered on in the game. Much of their power comes from this relationship, but games benefit too. No matter the underlying gameplay mechanics, games are highly visual. Their illustrations, from advertising posters to their cover art, empower them with greater visuality. Their machinic embodiments are often too limiting and can’t quite simulate the expressive power of the illustration.

It’s why the original Final Fantasy XIV failed. Those systems leaned on its art and the promise of cooperative play. But on the inside, the idea was nowhere to be found.

For more on the art of Final Fantasy, I recommend the art book Final Fantasy XIV: A Realm Reborn The Art of Eorzea - Another Dawn, which can be found at the Square Enix Online Store, as well as The Sky: The Art of Final Fantasy, available through Amazon.

You can check out an excellent feature on Akihiko Yoshida’s career by Ryan Lambie at http://www.denofgeek.com/games/bravely-default/28420/in-praise-of-akihiko-Yoshidas-videogame-fantasy-art.

An excellent Tumblr entitled Art of Akihiko Yoshida features much of Yoshida’s work and can be found at http://akihiko-yoshida.tumblr.com/.

The reference to the essay by Alexander Galloway comes from his article Gamic Action, Four Moments from the book Gaming: Essays on Algorithmic Culture, also available through Amazon.

Sources:

Amano, Yoshitaka. The Sky: The Art of Final Fantasy. Dark Horse Books, 23 July 2013.

“Art of Akihiko Yoshida.” Tumblr. Tumblr.com, n.d. Web. 14 December 2015. <http://akihiko-yoshida.tumblr.com/>.

“FFXIV Collector’s Edition Cover.” Final Fantasy Wiki. Wikia, n.d. Web. 13 December 2015. <Arthttp://finalfantasy.wikia.com/wiki/File:FFXIV_Collector's_Edition_Cover_Art.jpg>.

Final Fantasy XIV: A Realm Reborn The Art of Eorzea - Another Dawn. Square Enix, 2014.

“Final Fantasy XIV Online.” Metacritic. CBS Interactive, 2015. Web. 15 December 2015. <http://www.metacritic.com/game/pc/final-fantasy-xiv-online>.

Final Fantasy XIV: A Realm Reborn. Dir. Naoki Yoshida. Square Enix, 2013. Video Game.

Final Fantasy XIV Online. Dirs. Nobuaki Komoto and Naoki Yoshida. Square Enix, 2010. Video Game.

Galloway, Alexander. “Gamic Action, Four Moments.” Gaming: Essays on Algorithmic Culture.

Electronic Mediations (18): 1-38. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006. Print.

Lambie, Ryan. “In praise of Akihiko Yoshida’s videogame fantasy art.” Den of Geek. Dennis Publishing, 3, December, 2013. Web. 13 December 2015. <http://www.denofgeek.com/games/bravely-default/28420/in-praise-of-akihiko-Yoshidas-videogame-fantasy-art>.

Tactics Ogre: Let Us Cling Together. Dir. Yasumi Matsuno. Quest, 1995. Video Game.

Wouk, Kristofer. “Square Enix Announces Final fantasy XIV Has Over 5 Million Registered Users Worldwide.” Digital Trends. Digital Trends, 24 August 2015. Web. 13 December 2015. <http://www.digitaltrends.com/gaming/final-fantasy-xiv-5-million-users/>.